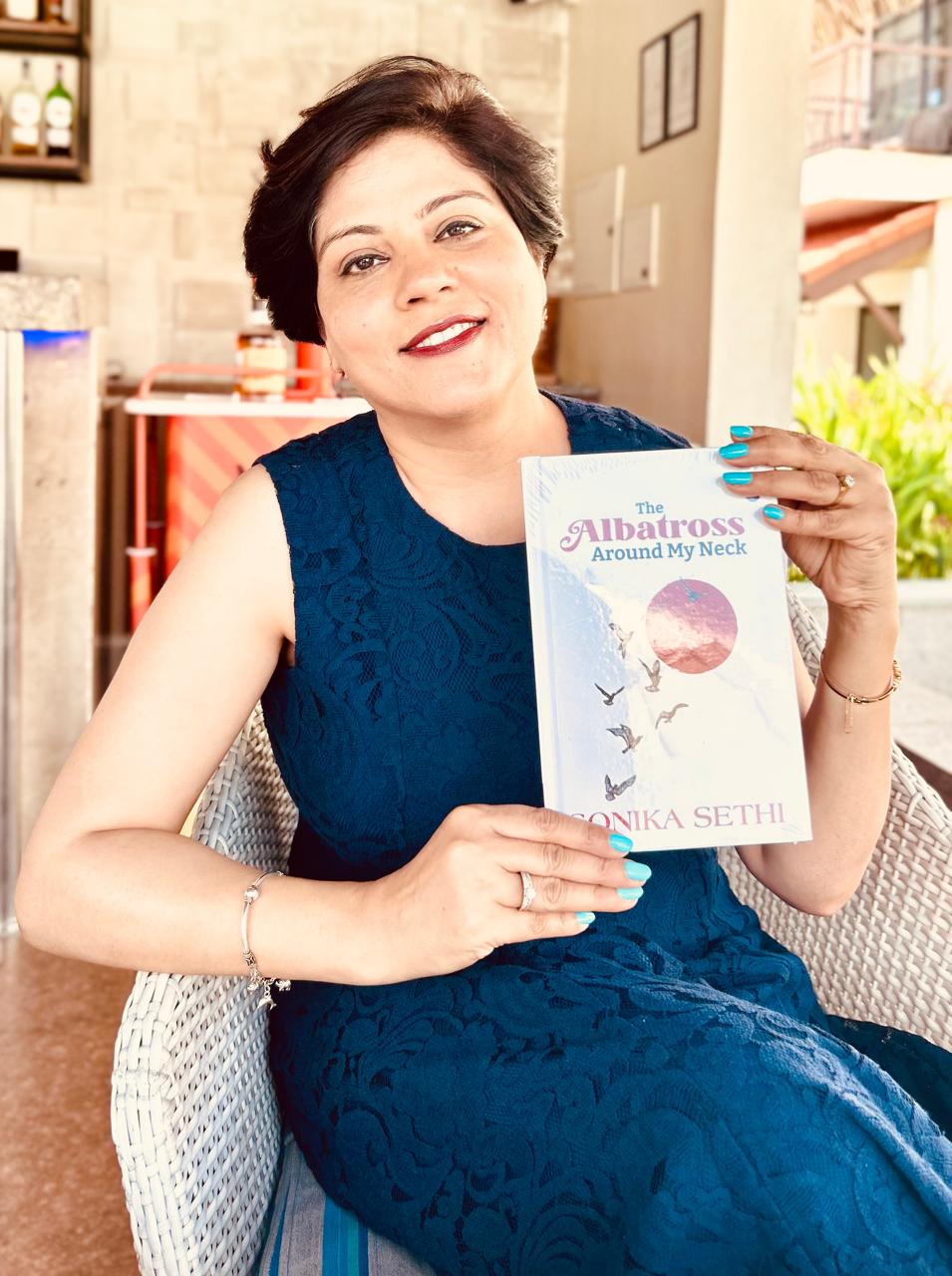

An Interview with Poet Sonika Sethi, on poetry and The Albatross Around My Neck

The following interview is with Author Sonika Sethi regarding her book The Albatross Around My Neck. Dr. Sonika Sethi is Associate Professor of English in SD College, Ambala Cantt. Her articles are regularly published in Hindustan Times, The Tribune, etc. She had been a gold medalist in M.A. English from Punjabi University, Patiala (Punjab) and she specialises in postcolonial literature, historical fiction and poetry. She is also the Executive Editor of the monthly literary magazine, Rhyvers Beat and has 11 books to her credit. The Albatross Around My Neck explores multiple facets of life and its array of emotions.

1. Tell me something about how you conceived the idea of the Albatross Around My Neck? Was it just the one title-accurate poem that brought out more in you? Or was it meticulously chalked out?

The idea of Albatross Around My Neck did not emerge as a single stroke of inspiration but rather as a gradual unveiling of emotions. The poem that lends its name to the book came first— it carried the weight of guilt, grief, and burdens unspoken. Once written, it seemed to demand companions, other poems that echoed different shades of vulnerability and strength. I did not sit down with a pre-mapped plan of seventy-five poems. Instead, the book evolved organically, with one poem opening a doorway to another. Some days, the writing was effortless, like a stream of consciousness. On others, it was deliberate and revisited with care. The “albatross” became a metaphor not just for one experience but for the many emotional inheritances we carry—love, passion, loss, separation. The book, then, is both an accident of feeling and an act of careful curation.

2. You’ve written 75 poems that explore themes such as love, passion, separation, and loneliness. Do you ever worry about overexposure or vulnerability while writing so intimately?

Writing poetry is an act of exposure— every line betrays something of the poet’s inner world. Yes, there are moments when I wonder whether I am revealing too much or standing too bare before the reader. But I remind myself that vulnerability is not weakness; it is strength disguised in fragility. By writing openly about love, passion, separation, and loneliness, I risk judgment, but I also invite empathy. The reader often discovers echoes of their own journey in my words, and this recognition makes the vulnerability worthwhile. Overexposure only worries me if the poems lose their authenticity or begin to sound rehearsed. Until then, I accept that poetry is not about self-protection but about connection. If my work creates even a fleeting bond between my rawest feelings and another’s lived reality, then the exposure has served its purpose.

3. You’ve written in several formats – articles, short stories. Yet, you chose this medium. What does poetry mean to you?

I have experimented with multiple forms— articles for structured thought, short stories for narrative exploration, and even essays for reflective commentary. Yet, poetry always feels like home. Its compactness allows me to distill complex emotions into a handful of words, without diluting their intensity. Poetry does not demand explanations; it thrives on silences, pauses, and unsaid meanings. For me, that freedom is intoxicating. Unlike prose, where clarity is king, poetry welcomes ambiguity, allowing readers to find their own truths within the lines. Poetry also mirrors the rhythm of thought and heartbeats— it is deeply personal yet universally resonant. When I write poems, I feel as though I am conversing directly with the soul, bypassing the noise of the rational world. It is, therefore, less a choice and more an instinct— poetry chooses me every time I need to express something that prose cannot hold.

4. Personally, “It’s your smile I dread” was the first poem I picked and by far, my favourite. It lays bare the two-faced identity of an abuser. What did you envisage while writing this poem in particular?

This poem was born out of a difficult reflection on duplicity— the paradox of the abuser who wears the mask of charm. I wanted to capture the unsettling truth that cruelty often hides behind tender gestures. Smiles, which we normally associate with warmth, can sometimes be loaded with menace when wielded by someone who manipulates. In this poem, I visualized the chilling duality of such an individual— the external grace and the internal darkness. My intent was not only to narrate a victim’s fear but also to make readers confront the uncomfortable reality that abuse rarely announces itself loudly; it tiptoes, cloaked in familiarity. The poem was my attempt to unmask that façade. Writing it was cathartic but also haunting, because it forced me to dwell on the disturbing contrast between love’s imagery and violence’s hidden presence. It remains one of my most emotionally charged works.

5. Some poems in your book are raw, unadulterated feelings, while some are lyrical in nature. What guides your decision to use a particular form for a poem?

The form a poem takes is never predetermined— it often emerges while I am in the act of writing. Some emotions resist containment; they burst forth raw, jagged, unpolished. Those poems remain sparse, almost journal-like, as though capturing a cry or confession. Others unfold lyrically, adopting rhythm and flow, as if the experience itself demands music. I allow the subject matter to dictate the form. Separation, for instance, often lends itself to fragmented, sharp verses, while passion prefers a gentler cadence. Sometimes I consciously revise a piece to fit a particular style, but more often, the form chooses itself. I see it as listening to the pulse of the emotion and respecting its demand. Just as no two moments of love or grief feel alike, no two poems should wear the same garment. Form, to me, is a servant of feeling, not its master.

6. How do you hope young readers, who are new to poetry, will engage with Albatross Around My Neck?

For young readers new to poetry, I hope Albatross Around My Neck becomes an accessible doorway rather than a closed chamber. Poetry can often feel intimidating, burdened by heavy metaphors or rigid traditions. My intention was to write in a way that feels intimate, conversational, and emotionally real. I want young readers to see that poetry is not about decoding hidden meanings for an exam, but about feeling something stir within. Whether it’s joy, sorrow, or recognition, the engagement lies in resonance rather than comprehension. I hope they approach the book as they might a diary— flipping to random pages, finding lines that speak to their current mood, and perhaps revisiting the same poem differently at another stage in life. If the collection nurtures curiosity and dismantles fear of poetry, then I would consider my work successful with the younger audience.

7. Do you think poetry today still holds the same power of expression as in the past, especially in a fast-paced digital world?

Poetry has always been a vessel of distilled truth, and I believe it continues to hold that power, even in today’s hyper-digital landscape. While attention spans are said to be shrinking, the irony is that poetry, with its brevity, fits beautifully into this pace. A short verse can travel faster, resonate wider, and linger longer than pages of prose. Digital platforms have also revived poetry, giving it newer audiences and forms of expression— spoken word videos, Instagram posts, reels. Yet, its essence remains unchanged: to give shape to emotions and provide language to what is often unspeakable. In times of speed and distraction, poetry acts as a pause, a stillness we carry in our pockets. It may no longer be recited in drawing rooms or salons, but its accessibility has broadened. The power of poetry lies not in its audience size, but in its capacity to move even one soul.